Teksty

Malarz w teatrze…

MAŁGORZATA ABRAMOWICZ

Teatr zna od podszewki, trafił do niego jako student Państwowej Szkoły Sztuk Pięknych w Gdańsku. W czasie studiów współpracował z działającymi przy Klubie Studenckim ŻAK Teatrem Rozmów i Studenckim Teatrzykiem Kontrapunkt. Wtedy nauczył się współodpowiedzialności, tego, że na sukces pracują wszyscy, aktorzy, reżyser, scenograf, pracownicy techniczni, oświetleniowcy. Jeszcze jako student Markowicz pracował w Teatrze Wybrzeże przy realizacji Tragedii o bogaczu i Łazarzu Anonima Gdańskiego. Zaprojektowana przez Mariana Kołodzieja monumentalna dekoracja wymagała skopiowania Sądu Ostatecznego Hansa Memlinga i właśnie tę robotę powierzono Markowiczowi i jego koledze. Tak zaczęło się poznawanie teatru profesjonalnego, nauka praktyczna rzemiosła. I choć dyplom zrobił z malarstwa w pracowni prof. Władysława Jackiewicza to teatr stał się jego prawdziwym żywiołem. Bardzo szybko stworzył swój, niepowtarzalny język, najlepiej rozpoznawalny wtedy, gdy pracował sam jako scenograf i reżyser. Stosowane przez niego kody plastyczne i interpretacja tekstu współgrały wówczas idealnie, wynikała z nich myśl przewodnia, intencja artystyczna, a to przecież w sztuce teatru najważniejsze. Pierwszą taką realizacją był Gyubal Wahazar Stanisława Ignacego Witkiewicza (1977, Teatr Polski w Bielsku Białej). W programie do tego spektaklu Markowicz określił swoje credo artystyczne: „scenografia jest sztuką, w której staram się wyrazić to co mnie w malarstwie i teatrze najbardziej fascynuje, plastyka powinna współinscenizować przedstawienie, powinna przylegać do tekstu dramatycznego, do gry aktorskiej, współtworzyć ogólny nastrój przedstawienia – a nie być tylko ilustracyjnym dopełnieniem całości. Przy pomocy obrazów i wizji można trafić w nieznane możliwości percepcji widza…”. I tak właśnie skonstruował Gyubala Wahazara, spektakl, za który zdobył wyróżnienie Klubu Krytyki Teatralnej. Była to także pierwsza realizacja tekstu autora, który stał się jego ulubionym dramatopisarzem. Markowicz mówił: „sądzę, że ukazując problemy ludzkie poprzez tragiczną groteskę, można uzyskać większy wstrząs. Witkacy, Gombrowicz czy Pirandello – w moim odczuciu, pokazując błazeńską rzeczywistość, mówią więcej – i może wbrew pozorom przystępniej niż tani realiści. W ten sposób można też bardziej wstrząsnąć sumieniem niż mówiąc rzeczy poważne wprost”. A ponieważ sam patrzy na świat z ironicznym dystansem, więc wyczuwa zawarte w tekstach groteskowe czy surrealistyczne subtelności, intencje i aluzje, potrafił je świetnie wykorzystać w swoich scenicznych opowieściach. Obserwująca od lat twórczość Markowicza Agnieszka Koecher-Hensel, (historyk i krytyk teatru) zauważyła, że artysta w charakterystyczny tylko dla siebie sposób interpretował Witkacego, tworzył specyficznych bohaterów, typy powtarzalne, a jednocześnie uniwersalne, które wyraźnie określał znakiem plastycznym, kostiumem, scenografią. Sam mówił: „Inwencja, w moim pojęciu, powinna w tym wypadku znaleźć ujście w wariacjach, zmianach detali. Ale są to odmiany wzoru, jego powtórzenia i przekształcenia”. Równie chętnie Markowicz realizował teksty Stanisława Mrożka, opracowywał je kilkanaście razy, a swój pomysł realizacyjny spektaklu Pieszo (Toruń 1981) omawiał z dramatopisarzem w Paryżu. Impresyjny tekst Mrożka Markowicz włożył, za zgodą autora, w metaforyczne koło historii, jak u Malczewskiego. Precyzyjna konstrukcja spodobała się nie tylko Mrożkowi, ale także publiczności i dziennikarzom na XXII Festiwalu Teatrów Polski Północnej w Toruniu. „Gazeta Pomorska” uznała ten spektakl za najlepszy z wówczas prezentowanych. Artysta sięgał także po teksty Ghelderode’a oraz klasyków, m. in. Szekspira. To także jego ulubieni dramatopisarze dzięki proponowanej estetyce teatralnej, „w której groteska jest naczelną kategorią struktury świata, widzianego jak absurdalna scena, gra marionetek”.

Markowicz zrealizował około sto pięćdziesiąt scenografii, pracował w teatrach w całej Polsce, był zapraszany za granicę. Jego projekty scenograficzne pokazywane były na licznych wystawach, zdobył wiele nagród. Nigdy nie należał do artystów pokornych, zawsze doskonale wiedział, co i jak chce na scenie opowiedzieć, nie znosił kompromisów i drogi na skróty. Pełen pasji i temperamentu konsekwentnie kreuje swoje trójwymiarowe obrazy, świadomie, z rozmachem „nie tylko buduje przestrzeń, działa kolorem, ale i tworzy znaczenia zasadnicze dla interpretacji całości: z jednej strony dookreśla tekst główny przedstawienia, akcentując jego wybrane elementy, organizuje je przestrzennie, ustalając ich wzajemne relacje, z drugiej zaś sztuka scenograficzna tekst przedstawienia interpretuje, narzucając odbiorcy – środkami plastycznymi – główną myśl dzieła”.

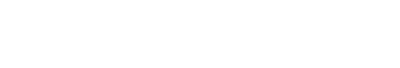

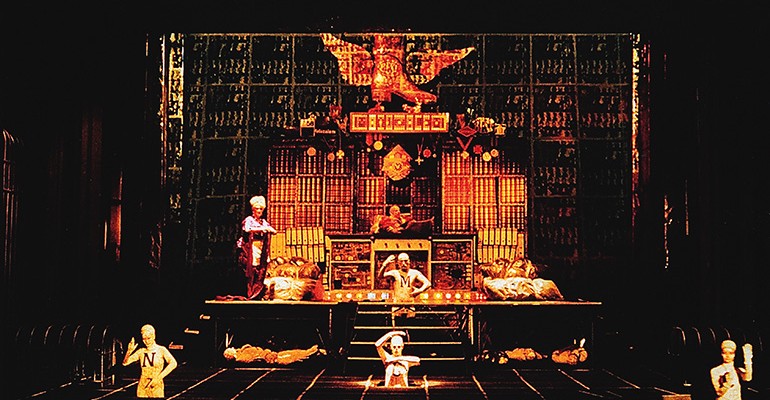

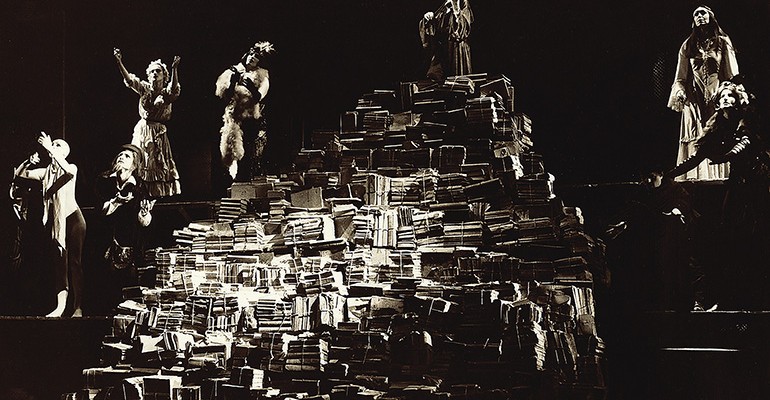

Lubił osaczać aktorów, zagęszczać atmosferę poprzez nagromadzenie detali, przedmiotów, szczegółów architektonicznych. W ten sposób komentuje tekst, tworzył znaki, które od razu określały bohaterów i akcję, jak na przykład w Emigrantach S. Mrożka, gdy zaproponował jako teren akcji brudną, szarą piwnicę z labiryntem rur na ścianach, splątanych kabli i przewodów, oświetloną gołą żarówką, ze stołem przykrytym gazetami i dwoma łóżkami. Pod jedno z nich wcisnął starą, tekturową walizkę, pod drugie – skórzany neseser. Już w warstwie plastycznej pojawia się konflikt, a splątane elementy dekoracji wyraźnie wskazują zawiłość sytuacji. Na scenie „maluje”, jest wrażliwy na kolor, formę, fakturę, komponuje obrazy z przeróżnych elementów, wielkich i małych, kukieł, przedmiotów i ludzi-aktorów. Wszystko jest tworzywem malarskim – zestawia, kontrastuje, tworzy przestrzenie metaforyczne, o niezwykłym klimacie poetyckim. Aktorzy też są dla niego plastycznymi znakami. W swoich inscenizacjach najczęściej traktuje ich jak element scenografii, przypominają craigowskie nadmarionety, zmechanizowane, zakomponowane w sposobie poruszania się, geście, sposobie mówienia (Gyubal Wahazar, Bezimienne dzieło, Powrót Błazna). Jednak artysta nie odbiera im głosu, jak inni twórcy tzw. teatru plastycznego, na przykład Leszek Mądzik. Markowicz świetnie słyszy tekst, potrafi go zestroić z obrazem, zakomponować spektakl z wizji i fonii i znakomicie go oświetlić, podbić nastrój, wydobyć ukryte sensy, prowadzić widza w głąb swojej artystycznej wyobraźni.

Józef Szajna, który zaprosił do współpracy młodego-gniewnego artystę, za jakiego uznawano wtedy Markowicza (w Teatrze Studio zrealizował wówczas jako scenograf i reżyser dwa spektakle: Matuzalem czyli wieczny mieszczanin, Y. Goll, prapremiera polska 30 IV 1977 i Giganci z gór, L. Pirandello, premiera 30 IV 1978) napisał o nim: „nie ilustruje wnętrz ani pejzaży, nie dekoruje sceny, ale drapieżnie ukazuje swój niepowtarzalny świat w poetyckim wymiarze metafory. Bo sztuka Markowicza powstaje z ducha malarza, a nie architekta. Często zagęszcza on przestrzeń sceniczną formami różnej wielkości, rekwizytami i kukłami wypełniającymi scenę, tworzy obrazy żywymi aktorami, buduje świat procesji i zbiorowych scen układających się w narrację wizualną. Poprzez ruch tworzy swój barokowy teatr wydarzeń niepodobnych do codzienności. Scena jest miejscem atelier Markowicza, jego pracownią malarską, jakby w obrazie chciał artysta zamknąć wystawiany dramat”.

Kilka swoich spektakli artysta zrealizował w teatrze lalek Miniatura, Gdańsk (Wędrówki Mistrza Kościeja, Kram Karoliny, Powrót Błazna) i choć nie są to spektakle lalkowe, to zdecydowanie są to spektakle „plastyczne”, bo i rekwizyt, i dekoracja są współpartnerami aktorów, a oni sami „zaprogramowani” są przez twórcę jak nadmarionety, ni to ludzie, ni to lalki, umieszczone na tle ściany z twarzy-masek (Powrót Błazna, scenariusz, reżyseria, scenografia – Andrzej Markowicz), które, jak chór antyczny, komentują wydarzenia sceniczne, odsyłając widzów do gombrowiczowskiej wojny na miny czy do „typów wywiedzionych z obrazów Breughla czy Boscha, patronów artystycznych Ghelderode’a. Do nich też odwołuje się Markowicz, oczarowując widza urodą malarskich obrazów”.

Swoje doświadczenia przełożył prof. Andrzej Markowicz na program zajęć Międzywydziałowej Pracowni Scenografii w Akademii Sztuk Pięknych w Gdańsku, ciekawy i wszechstronny, umożliwiający studentom zdobycie wiedzy teoretycznej i przede wszystkim praktycznej. Scenografia jest sztuką, która łączy różne dziedziny, studenci muszą więc nauczyć się operować światłem, kolorem, bryłą, ruchem, a wszystko to podporządkować słowu, opowieści, muszą nauczyć się kompozycji i rozumnego łączenia wszystkich elementów. Nie jest dla Markowicza istotne, czy projekty przygotowywane są w sposób tradycyjny czy za pomocą nowych mediów, natomiast ważne jest, by miały one sens merytoryczny i były opracowane sprawnie pod względem technicznym. Wiele razy powtarzał, że dla niego teatr, ale i cała sztuka, to przede wszystkim kreowanie znaczeń, koncepcja myślowa. Sztuka musi przemawiać do widza, może dawać mu rozrywkę, może nim wstrząsać, ale przede wszystkim musi pozwalać mu na refleksję, która prowadzi do zrozumienia świata i człowieka. Stara się, aby nie bezsensowne nowinki (ukrywające często niemoc twórczą i płytkość umysłową), a rzeczywiste, wartościowe współczesne dokonania były przedmiotem zainteresowania studentów. Dzięki profesorowi jego uczniowie mogli zderzyć się z prawdziwym teatrem, zajrzeć za kulisy, poznać specyfikę wszystkich typów scen, obserwować pracę przy powstawaniu scenografii, spróbować własnych sił.

Dla Andrzeja Markowicza praca ze studentami zdaje się być równie pasjonująca jak praca w teatrze. Często mówi, że jest jego ogromną, osobistą „belferską” satysfakcją, że w tak krótkim okresie powstała grupa młodych artystów, którzy poziomem swoich prac zasłużyli na to, aby traktować ich jak profesjonalistów. I właśnie ich, swoich byłych studentów zaprosił do wspólnej wystawy…

A painter at the theatre…

He is familiar with the ins and outs of theatre, where he started still as a student of the State Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. During his studies he cooperated with Teatr Rozmów and Kontrapunkt student theatre, operating at ŻAK Student Club. There he learned co-responsibility and that success is the fruit of everybody’s joint effort – that of the director, the scenographer, technical staff, light operators. Ev en as a student Markowicz worked at Wybrzeże Theatre, preparing the staging of Tragedy on the Rich Man and Lazarus by Anonim Gdański. The monumental decorations designed by Marian Kołodziej required making a copy of The Last Judgment by Hans Memling, and the task was assigned to Markowicz and his colleague. That was how he became familiar with professional theatre, learning the practical aspects of the art. Although he graduated from prof. Władysław Jackiewicz’s painting studio, theatre became his true element. He quickly shaped his own unique language, most recognizable whenever he worked alone as both scenographer and director. The plastic codes and text interpretation used by Markowicz interacted perfectly, there was a common keynote, an artistic intention, which is in fact the most important aspect of theatre. His first such project was Gyubal Wahazar by Stanisław Ignacy Witkiewicz (1977, Polski Theatre in Bielsko Biała). In the program to the performance Markowicz defined his artistic credo: “scenography is an art by means of which I try to express what fascinates me most in painting and theatre. The plastic aspect should co-stage the play, it should be juxtaposed to the dramatic text, to the artists’ efforts, it should contribute to the general ambience of the performance – instead of being simply an illustrative completion of the whole. By using images and visions, one can touch the unknown perceptive potential of the audience…”. Gyubal Wahazar was staged according to that principle and the performance was awarded a distinction by the Theatre Critic Club. It was also Markowicz’s first staging of a text by the author who became his favourite playwright. Markowicz said: “I believe that by depicting human problems using tragic grotesque, we can shock the audience more strongly. Witkacy, Gombrowicz or Pirandello – in my opinion by presenting clownish reality they express more than cheap realists, and maybe paradoxically in a more accessible way. Thus we can also shake conscience more than by putting serious things straight. ” Markowicz himself perceives the world with an ironic distance, so he is able to grasp grotesque or surreal subtleties, intentions and allusions and he knows how to use them perfectly in his stage stories. Agnieszka Koecher-Hensel (theatre historian and critic), an observer of Markowicz’s work for many years, noticed that he interpreted Witkacy in a characteristic unique way, creating distinctive protagonists, reproducible but at the same time universal types, clearly identifiable by a plastic sign, costume, scenography. He himself said: “Invention, in my opinion, should in this case find its outlet in variations, detail changes. However, these are variations of a pattern, its repetitions and reconstructions”. Markowicz was just as keen on working on Stanisław Mrożek’s texts. He prepared a dozen such realizations and his idea of staging On Foot (Toruń 1981) was debated with the playwright in Paris. Mrożek’s impressive text was inscribed, upon approval by the author, in the metaphoric circle of history, as in Malczewski’s works. The precise construction pleased not only Mrożek, but the audience and journalists at the 22nd Northern Poland Theatre Festival in Toruń. “Gazeta Pomorska” recognized it as the best performance of the Festival. The artist also reached for Ghelderode’s texts, as well as classics such as Shakespeare. They belong to his favourite playwrights due to the suggested theatre esthetics “where grotesque is the leading category of the world’s structure, perceived as an absurd stage, a marionette play”.

Markowicz completed around 150 scenographic projects, working in theatres all over Poland and invited abroad. His projects were presented at many exhibitions and he received numerous awards. He never belonged to the category of humble artists, as he always knew perfectly what and how he wanted to tell on stage. He hated compromise and shortcuts. Full of passion and temperament, he consistently creates his three-dimensional images, acting consciously and with momentum, “not only constructing space, using colours, but also creating meanings which are fundamental to the interpretation of the whole, thus scenography on the one hand adds precision to the leading text of the performance, emphasizing its selected aspects, organizing them spatially, determining their mutual relations, on the other hand, it interprets the text of the play, imposing on the audience the guiding thought of the work, using plastic means”.

He liked to smother actors, to thicken the atmosphere by accumulating detail, objects, architectural elements. By commenting on the text in such a way, he created marks which immediately defined the characters and the plot, as in The Émigrés by S. Mrożek, where he suggested the scenery of a dirty grey basement with a labyrinth of pipes, intertwined wires and cables on the walls, lit by a bare bulb, with a table covered with newspapers, and two beds, an old cardboard suitcase under the one, a leather briefcase under the other. Even in the plastic aspect there is already a conflict, and the intertwined decorations clearly indicate the complexity of the situation. He “paints” on stage, he is sensitive to colour, shape, texture, he composes paintings using different elements large and small, puppets, objects and people-actors. Everything is a painter’s material – he juxtaposes, contrasts, creates metaphoric spaces with an incredible poetic ambience. Actors are also plastic marks, in his projects he treats them as scenographic elements, resembling Craig’s supermarionettes, mechanized, composed in their movements, gestures, way of speaking (Gyubal Wahazar, The Anonymous Work, The Return of a Clown). However, the artist does not deprive them of their voice like other authors of the so-called plastic theatre, such as Leszek Mądzik. Markowicz hears the text wonderfully, he is able to tune it in with the image, compose a performance made of vision and sound and light it perfectly, building up the atmosphere, revealing hidden messages, guiding the audience into the depths of his artistic imagination.

Józef Szajna, who invited the angry young artist (as Markowicz was then perceived) to Studio Theatre, where he staged two plays as scenographer and director (Methusalem or the Eternal Bourgeois, Y. Goll, Polish premiere on 30. 04. 1977 and The Mountain Giants, L. Pirandello, premiere on 30. 04. 1978) wrote about him: “he does not illustrate interiors or landscapes, he does not decorate the stage, but rapaciously depicts his unique world in the poetic metaphoric dimension. For Markowicz’s art is created by the soul of a painter, not that of an architect. Often stage space is thickened by shapes of different sizes, by props and puppets filling up the stage, paintings are created using live actors, a world of processions and collective scenes is shaped, forming a visual narration. Through movement, Markowicz creates his baroque theatre of events which do not resemble reality. The stage is Markowicz’s workshop, his painting studio, as if the artist wanted to encapsulate the play he is staging in a painting”.

Some of his projects were completed at puppet theatres Miniatura, Gdańsk (La Balade du Grand Macabre, Caroline’s Household, The Return of a Clown) and although they are not puppet plays, they definitely are “plastic” stagings, as the props and decorations are the actors’ half-partners, and the actors themselves have been “programmed” by the author as supermarionettes, neither human beings, nor puppets, placed on the background of a wall composed of faces-masks (Return of a Clown, script, direction, scenography by Andrzej Markowicz), which like the ancient choir comment on the events on stage, referring the audience to Gombrowicz’s war of facial expressions or to “types drawn from paintings by Breughl or Bosch, Ghelderode’s artistic patrons. Markowicz also refers to them by enchanting the audience with the beauty of visions resembling paintings. ”

Prof. Andrzej Markowicz translated his experience into his lectures at the Interdisciplinary Scenography Studio at the Academy of Fine Arts in Gdańsk. The programme was interesting and multidimensional, enabling the students to gain theoretical, but above all practical knowledge. Scenography is an art combining various areas and students need to learn to operate light, colour, shape, movement, and to subject them all to the word, the story, they must learn composition and an intelligent combination of all elements. It is of no importance to Markowicz whether the projects are prepared in a traditional way or using modern media, but it is crucial that they should have a substantive meaning and be technically efficient. He repeated many times that for him theatre, but any art in fact, was fundamentally the creation of meanings, a thought concept. Art must speak to the audience, it may provide entertainment, it may shock them, but above all it must make them reflect, which leads to a better understanding of the world and of man. He tries to attract students to true, valuable modern achievements, instead of nonsensical novelties (often disguising creative impotence and intellectual shallowness). The professor gave his students an opportunity to face real theatre, to look behind the scenes, to become familiar with all types of stages, to observe the work of a scenographer, to test their skills.

For Andrzej Markowicz, working with students seems as fascinating as working at the theatre. He often says that he is filled with huge personal satisfaction as a teacher by the fact that within such a short period of time a group of young artists was created who deserve to be treated as professionals due to the high quality of their works. And he invited them – his former students to participate in a joint exhibition…

© 2014 Andrzej Markowicz Logowanie